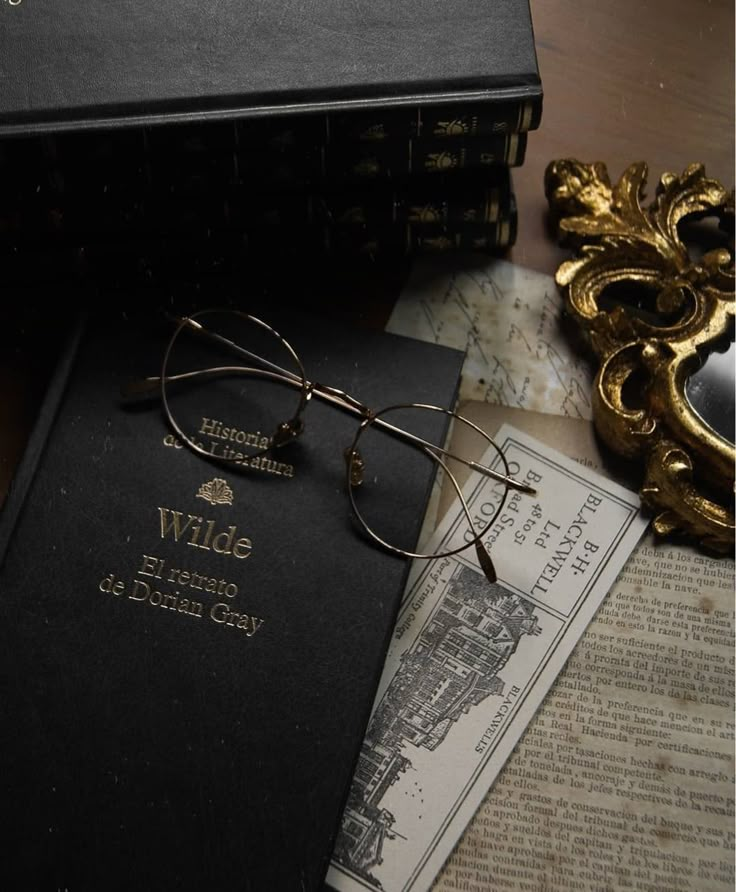

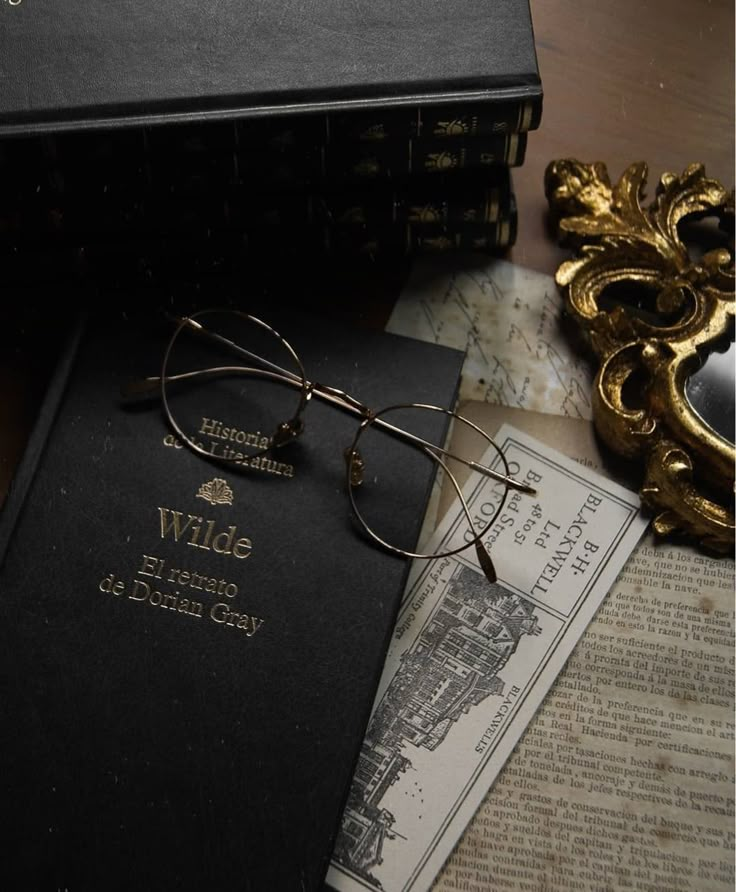

there is something deeply unsettling about beauty – how it lingers like an illusion, captivating and fleeting, always tethered to its inevitable companion: decay. it’s a tension we all live with, whether we acknowledge it or not. in the age of filters, plastic surgery, and endless cosmetic rituals, beauty feels more like a fragile construction than ever before, an ideal that can never truly be attained but must always be chased. oscar wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray explored this interplay long before our current obsession, yet the core of his message remains strikingly relevant today.beauty, as we’ve been taught to define it, is an image frozen in time, something to be revered, desired, and preserved. it is a standard, both fragile and unyielding, one that demands we sacrifice parts of ourselves to meet it. beneath its polished surface, however, there is a quiet decay, a truth often ignored. in wilde’s story, dorian’s portrait does not merely reflect his image – it holds the truth of his inner decay, his moral degradation, while his outward beauty remains flawless. the portrait, untouched by the ravages of time, is the only real record of what happens to us when we worship beauty and refuse to acknowledge the cost. today, we are all dorian gray. we live in a world where beauty is consumed, packaged, and sold to us daily. but the cost is not just about skin-deep imperfections. it’s a deeper, more insidious cost – one that shows itself in the way we are taught to value only what is visible, to cherish only the flawless exterior. we ignore the decay of identity, of the soul, of our self-worth, when we subscribe to a beauty standard that is ultimately unattainable and oppressive. and yet, in some ways, we continue to seek beauty – because what else is there? beauty has power, it demands attention, it commands admiration. in a world that so often values youth over wisdom, appearance over substance, beauty becomes a currency, even as it decays. it is a paradox – an essential part of the social fabric, yet toxic in its very nature. it’s easy to criticize this obsession, to see how it keeps us trapped in a cycle of self-rejection, of longing for something we can never fully be. but to discard beauty entirely would be to deny its complexity, its potential to empower, to challenge, and to express. the truth is, beauty cannot exist without decay. it is a constant interplay, a tension we cannot resolve. beauty, in its most pure form, is fleeting, ephemeral. like the first blossom of spring, it bursts into existence only to fade. the decay is not always ugly, though – in the decay, there is transformation. we see it in nature, in art, in people who grow older with grace, embracing their scars, their lines, their imperfections. beauty and decay are not opposing forces; they are partners in a cycle we cannot escape. perhaps the most important thing we can do, then, is to redefine beauty. to move beyond the surface and acknowledge the decay – not as something to be feared or hidden, but as something to be honored. in accepting that decay is inevitable, we begin to understand beauty as something more dynamic, more truthful. it’s not the frozen, flawless image we’ve been taught to worship, but something more profound, more real. it is not the beauty of a perfect face, but the beauty of resilience, of imperfection, of evolution. today, we must embrace the truth that beauty is not an object to be possessed but a force to be understood. we must acknowledge the decay that follows beauty’s fleeting bloom, but not with shame or fear. instead, let us see it as a necessary part of the human experience, a cycle of growth and change. beauty, like everything else, is transient – and that is what makes it valuable.

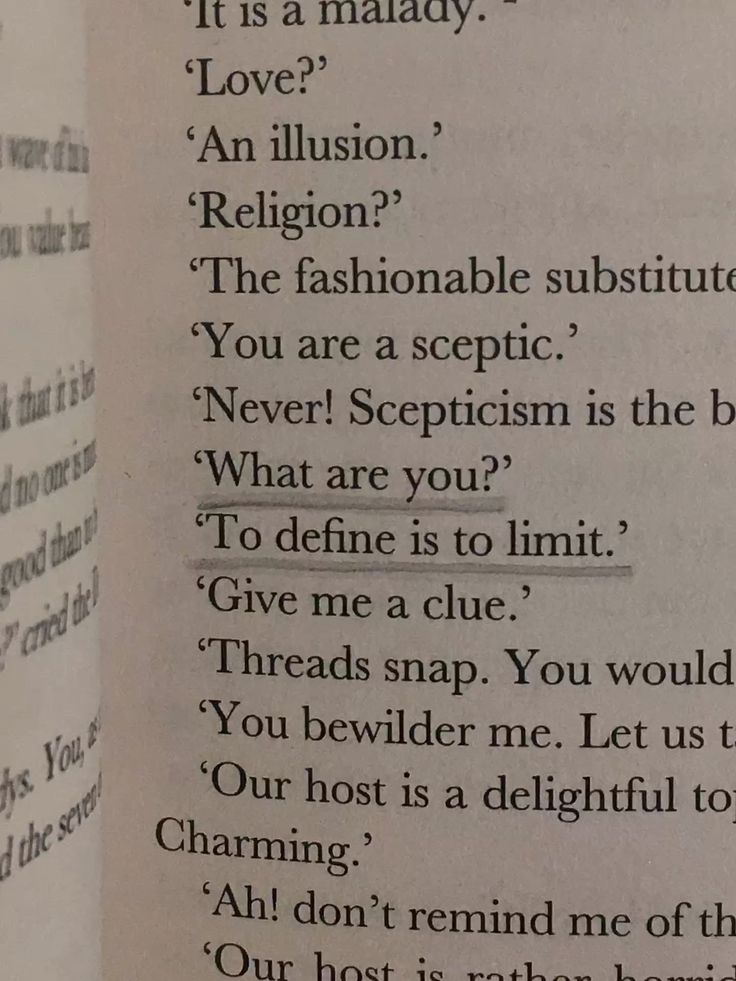

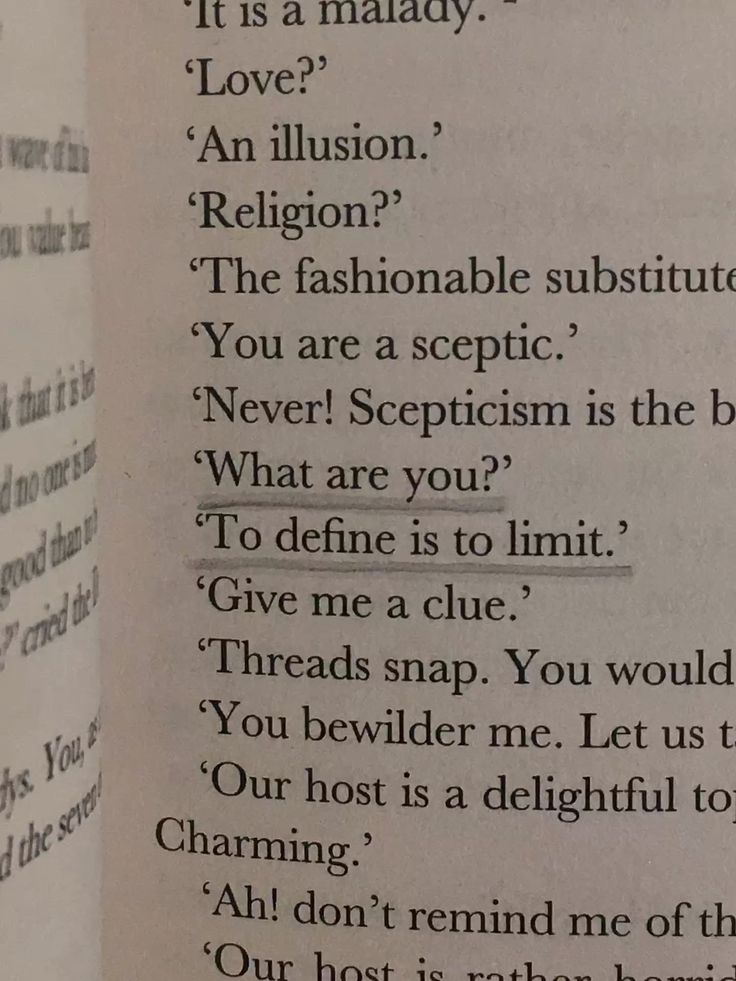

hedonism and aestheticism, though often seen as indulgent or self-serving, are far more nuanced philosophies than they are sometimes given credit for. both are rooted in the pursuit of pleasure and beauty, yet they take radically different approaches to achieving and experiencing them. in today’s world, where consumption, instant gratification, and a relentless quest for self-optimization dominate, these philosophies feel eerily relevant. they challenge us to question what we truly seek, and why. hedonism, at its core, is the philosophy that pleasure – physical, emotional, intellectual – is the highest good. it invites us to seek out what makes us feel good, to indulge in experiences that bring satisfaction. this might seem shallow on the surface, but a closer look reveals a deeper longing for freedom from suffering, a desire to live fully in the moment. it is a rebellion against asceticism, against the idea that virtue lies in denial. hedonism tells us that to be human is to experience joy, to embrace the fleeting moments of euphoria, even if they are temporary. but in our modern context, hedonism is often reduced to an endless cycle of consumption, where pleasure becomes synonymous with excess – shopping sprees, parties, fleeting relationships, binge-watching, and instant gratification. it can feel like we’re stuck in a loop, chasing the next thrill with no deeper sense of meaning. this is where the philosophy’s true depth gets lost: in its more sophisticated forms, hedonism asks us to seek not just pleasure, but the right kind of pleasure – the kind that nourishes the mind, body, and soul, without leaving us hollow afterward. then, there is aestheticism, the philosophy that beauty, rather than pleasure, is the highest aim in life. aestheticism believes that life should be lived as an art form, with beauty being both a pursuit and a way of experiencing the world. the aesthete seeks out harmony, form, and elegance, whether in art, nature, or human interaction. art for art’s sake is the central tenet, rejecting any notion that art or beauty should be used for moral, social, or political purposes. beauty itself, in the aesthetic view, holds intrinsic value. it is not about what it can do for society or how it can serve some greater function, but simply that it is beautiful, and in that beauty, we find meaning. where hedonism is concerned with the transient nature of pleasure, aestheticism holds beauty as timeless, existing outside the constraints of the everyday. in today’s hyper-visual culture, aestheticism often translates into a curated, Instagram-worthy life, where beauty is packaged and consumed with the same speed as any other commodity. but to reduce aestheticism to shallow displays of beauty misses the point of the philosophy entirely. true aestheticism is about transcending the mundane, cultivating an appreciation for the depth and nuance of beauty in its many forms. it is about finding art, grace, and meaning in the world, regardless of whether it serves a practical purpose or fits within the bounds of traditional moralities. both philosophies, at their heart, invite us to think about how we experience the world. they challenge the idea that life should be lived by strict moral codes or that true fulfillment lies in sacrifice and suffering. hedonism invites us to embrace our desires, while aestheticism teaches us to appreciate beauty for its own sake. the issue, however, arises when these philosophies are co-opted by consumerism, when pleasure becomes a product to be consumed without thought, or when beauty is reduced to the superficial. in such cases, both hedonism and aestheticism lose their power to challenge and instead become merely tools of distraction. perhaps the key lies in balance. a life driven by pure hedonism without self-awareness or contemplation can quickly spiral into emptiness. similarly, a life devoted only to beauty without any deeper connection to meaning can feel hollow. the challenge, then, is to seek pleasure and beauty not as ends in themselves, but as means to enrich the human experience. we must be conscious of what we seek, why we seek it, and what it ultimately brings to our lives. hedonism and aestheticism should not be an escape from the real world, but an invitation to engage more fully with it, to elevate our senses, to transform our experiences into something more than mere moments of gratification. in a society where both pleasure and beauty are so often commodified, it is easy to lose sight of the deeper aspects of these philosophies. to live hedonistically is not to consume mindlessly, but to seek pleasure that nourishes; to live aesthetically is not to idolize the superficial, but to see beauty in the world with eyes unclouded by societal expectations. both philosophies, when understood in their truest forms, have the potential to offer us a more meaningful, more connected existence..

in The Picture of Dorian Gray, wilde masterfully weaves a narrative that challenges us to confront the struggle between good and evil, morality and corruption. it’s a story not just about the superficial allure of beauty, but about the deeper consequences of our choices, both seen and unseen. we all make decisions every day, decisions that affect not only our lives but the lives of those around us. and yet, how often do we pause to consider the true impact of our actions? can we really separate our outward appearances from our true selves? are we, like dorian, capable of presenting one version of ourselves to the world while hiding something far darker beneath? the duality of human nature is at the heart of the novel. dorian gray, as the perfect example, embodies this contradiction. on the surface, he is the epitome of charm, beauty, and grace – a young man untouched by the harsh realities of life. yet, beneath that flawless exterior, a portrait grows increasingly grotesque, revealing the true nature of his soul. it’s as if wilde is asking whether it is possible to compartmentalize our goodness from our darker inclinations, to live a double life where the external remains pure while the internal festers. dorian’s portrait is both a symbol of his moral decay and a testament to the dissonance between appearance and reality. the idea that someone can be both good and evil at the same time is a compelling one, and one that sparks the deepest questions about the nature of identity. can we ever truly know ourselves? can we be both virtuous and corrupt? the story suggests that the human soul is not so easily categorized. we are all capable of good, but also capable of immense harm. the question isn’t whether we have the capacity for both good and evil, but whether we choose to embrace one over the other. perhaps what makes the struggle in The Picture of Dorian Gray so timeless is the way it forces us to confront the complexities of our own moral choices. when faced with temptation, how often do we pause to ask ourselves: how will this choice affect me in the long run? how can we ever truly separate the persona we project to the world from the reality of our inner selves? the tragedy of dorian’s life is that he never truly faces these questions. his refusal to acknowledge the consequences of his actions leads to his downfall, not because he is inherently evil, but because he denies the duality of his own nature. in the end, the novel reminds us that the choices we make – the ones that seem small at the time, the ones that go unnoticed – are the ones that define us. the battle between good and evil is not always a grand, dramatic war. sometimes, it’s the quiet moments of temptation, the private decisions we make in the dark, that shape who we truly are.